2019

2018

Featured

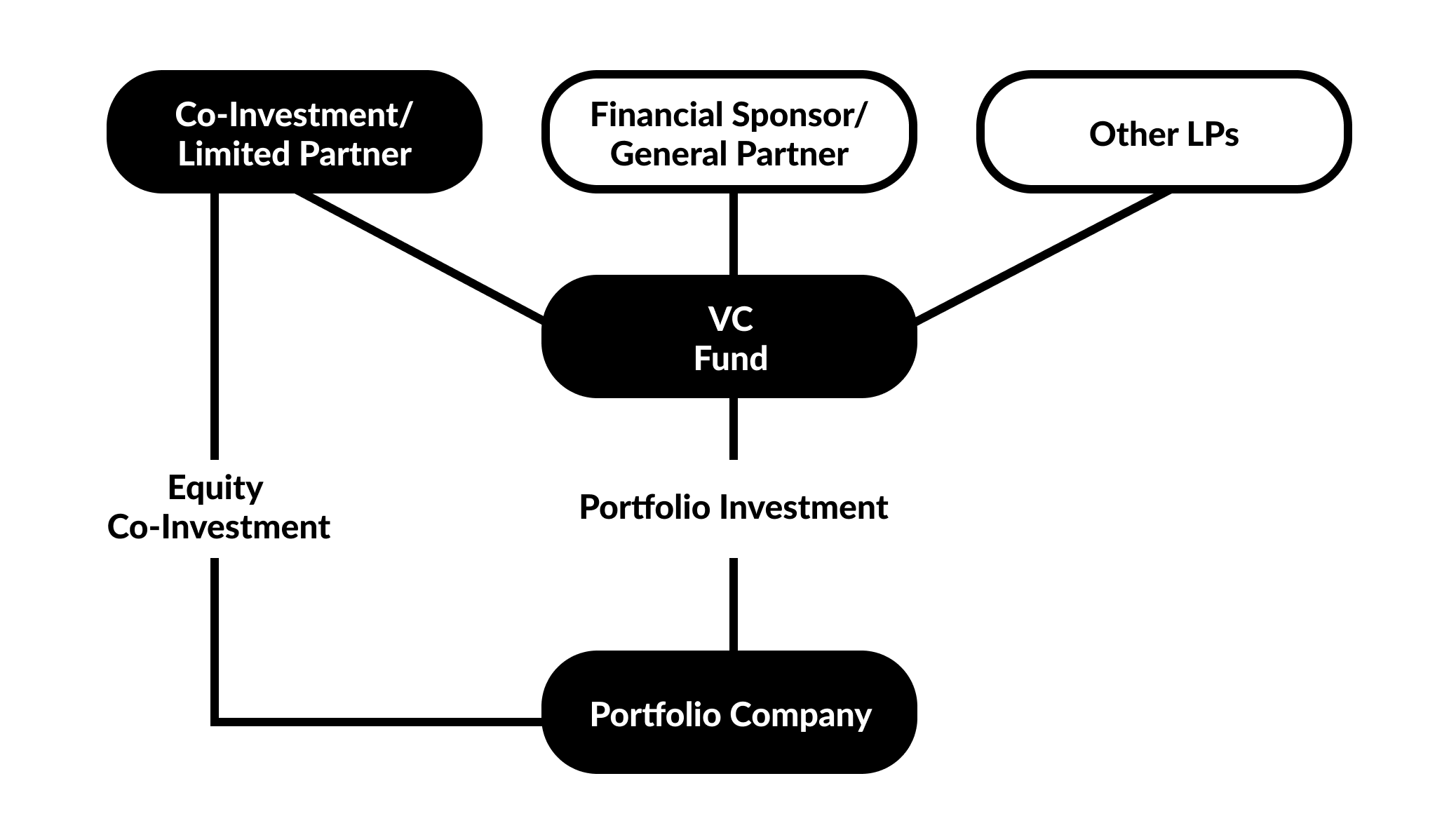

For private investors seeking maximum returns, co-investments are key to attractive investment multiples. Before we dig into the details, it is worthwhile to clarify the relevant terminology in this article:

A fund investment is an investment made by an LP into a VC/PE fund (e.g. Family Office invests in Venture Fund)

A co-investment is an investment where LPs allocate additional capital directly into companies alongside or following VC/PE investors (e.g. Venture Fund invests in Portfolio Company; Family Office also invests directly in this Portfolio Company)

A direct investment is an investment made directly into a private company without the participation or involvement of a VC/PE fund (e.g. Family Office invests in Startup; Startup is not in the portfolios of any of the Family Office’s invested Venture Funds)

Figure 1. Equity Co-investment & Direct Fund Investment Diagram

There are multiple benefits to co-investments. For one, you are able to gain more insight into portfolio companies through current fund exposure, data, and performance than you do with individual direct deals. You can cherry-pick the winners, increase your equity stake, and ultimately increase investment multiples. An added perk of co-investments is that they typically have zero or reduced fees (compared to the typical 2% management fee / 20% carry on fund investments). We can observe these benefits in the following chart:

Figure 2. Survey of fund managers comparing co-investment performance to fund returns

Source: Prequin

For GPs, offering co-investments provides them with an additional capital source to make larger investments. This can be particularly useful when a fund is close to being fully deployed and when follow-on capital requirements exceed reserves as per portfolio construction models. GPs typically only offer co-investments to anchor LPs and other LPs with whom they have an established relationship. This practice improves the overall marketability of the fund as LPs are provided more lucrative co-investment opportunities.

Figure 3. Co-investment vs. Direct Investment Deal Value (2012–2017)

Source: McKinsey, Pitchbook

With these benefits, co-investing activity has been rising in the past few years. According to McKinsey, co-investments have doubled from $45 billion to $104 billion since 2012 while direct fund investments have remained relatively stagnant. As more investors and fund managers recognize the benefits of co-investment opportunities, we can only expect this trend to continue.

That being said, while co-investment opportunities presented may seem favorable, LPs should still ensure that proper due diligence is conducted. Depending on the transaction size, these types of investments may disproportionately increase concentration relative to fund investments, as capital gets allocated into a single company rather than into a fund’s diversified portfolio. The associated risk should be carefully evaluated, both on an individual deal basis and as part of a broader portfolio.

If you are interested in learning more about equity co-investments and how LVAM can help with this process, free to contact us at lvam@laconiacapitalgroup.com.

Originally published in the April 2019 LVAM Newsletter.

$23 billion, $120 billion, $7.1 billion, $35 billion, $12 billion, and $41 billion. What do all these numbers have in common? They are valuations of some of the largest tech companies poised to enter Wall Street this year or next.

Lyft, Uber, Slack, Airbnb, Pinterest, Postmates, and Palantir were all founded roughly at the same time of the ‘08 financial crisis, and after a decade of investor pitches, regulatory pressures, and sleepless nights, these companies have almost “made it” to the big ranks. While these companies are poised to IPO this year or next, it is important to recognize that the road to their massive valuations was lengthy and not always smooth sailing.

Founding Dates of Unicorns Poised to IPO in 2019-2020

One of the most significant risks these companies have faced has been regulation — not surprising given that so many of them are industry disruptors. Uber, for instance, is the perfect example of a company that has been forced to strategically pivot in many markets due to roadblocks imposed by stakeholders such as the regulatory bodies or unions. In its early days, Uber struggled to operate in states with preexisting limo and taxi service laws. In Miami, the company was initially forced to charge a minimum of $80 per ride as it was classified as a limousine service; as a result, they chose not to operate there. Airbnb faced similar regulatory pressures in hospitality. Hotel worker union efforts have resulted in many forced compromises such as host restrictions in markets including NYC and Chicago.

In addition to regulation slowing down the time to IPO, the amount of dry capital deployed in VC has increased significantly. In previous generations, companies with valuations as high as these would have long resulted in an IPO or direct listing. However, there has been an influx of new capital. According to PitchBook, between 2009 and 2015, the number of US-based VC investments more than doubled from 4,487 to 10,740 with deal value almost quadrupling from $27.2 billion to $83 billion. This trend has led to longer time to liquidity in recent years as companies hold out for more venture capital to attract higher exit values.

Andy Rachleff, CEO of Wealthfront and Co-Founder of Benchmark, estimates that more than 6,000 shareholders of the upcoming IPOs will join the 7-digit club starting with Lyft’s IPO today. As the saying goes — high risk, high reward.

If you are interested in learning more about venture-backed IPOs, feel free to contact us at lvam@laconiacapitalgroup.com.

Originally published in the March 2019 LVAM Newsletter.

“How to hit home runs: I swing as hard as I can, and I try to swing right through the ball… The harder you grip the bat, the more you can swing it through the ball, and the farther the ball will go. I swing big, with everything I’ve got. I hit big or I miss big.” –Babe Ruth

Babe Ruth was one of America’s finest baseball batters, having played 22 seasons with 714 career home runs and 1,330 strikeouts out of 10,622 pitches. While venture capitalists face vastly different types of pitches, the home run mentality coined “the Babe Ruth effect” has seen widespread permanence throughout the venture industry. In Chris Dixon’s article, “The Babe Ruth Effect in Venture Capital,” he analyzes the performance of successful venture capital funds and determines that higher multiple fund performances are derived from higher proportions of investments returning >10x. As expected, there is also a strong correlation between investment return size and overall fund performance.

What makes the Babe Ruth effect difficult to come to terms with for many unfamiliar with the venture asset class is the high level of “strikeouts” that come with the strategy. Dixon analyzed the same cohort of funds and found that even funds with great performance had a relatively high proportion of investments that lost money.

A dangerous trend, especially with earlier funds, is emulating the investment strategies of billion dollar funds such as Sequoia, Andreessen Horowitz, and Softbank without building a differentiated competitive advantage. Often this imitation manifests itself in competition for “unicorns”, defined as privately held companies valued at over $1 billion. Regarding this “unicorn fever”, PitchBook noted that in 2018, startups achieved billion dollar valuations in less than 4.5 years, down from an approximate seven years in 2013. While unicorn valuations are nice to flaunt at dinner parties and are generally positively correlated to fund performance, there are many other key drivers of fund returns. What these funds need are not necessarily unicorns with billion-dollar valuations, but high exit multiples on select portfolio companies that can return the fund. Dan Primack, a business editor at Axios, recently tweeted:

One thing that I think gets lost in the VC vs. non-VC discussion is that VCs don't need a company to become a "unicorn." At least not the early-stage VCs. They might want it, but unicorns weren't really a thing until a few years back, and VCs "settled" for much shorter home runs

— Dan Primack (@danprimack) January 11, 2019

To Dan’s point, some key factors to consider when defining your investment strategy to hit multiples include (but are not limited to):

Ownership stake (driven by check sizes, pre-money valuations, pro rata rights, and follow-on reserve capital)

Projected exit value

Deal terms (such as liquidation preferences)

Portfolio company capital efficiency

Rather than hunting for unicorns, investors and fund managers should focus on conducting proper due diligence (market opportunity/size, capital efficiency, potential upside investment returns), obtaining attractive deal terms (ownership stake derived from investment size, initial valuation and available follow-on capital), and providing portfolio company support to achieve higher multiples at exit. It’s also critical for emerging funds to properly define their investment thesis from a stage, industry, and business model perspective, enabling them to hone in on a competitive offering.

In addition, if you are investing in venture funds, make sure they have a distinct strategy to capture a unique segment of the VC pie whether it be in sourcing, vertical expertise or post-investment value-add. If you are interested in learning more about the Babe Ruth effect and the world of unicorns, please feel free to contact us at lvam@laconiacapitalgroup.com.

Originally published in the February 2019 LVAM Newsletter.

Further Readings:

Venture capital traces its history to the mid-1940s when organized investing into developmental stage companies first began. Fast-forward 70 years, and ‘venture capital’ is an umbrella term for a large and multifaceted industry.

Total invested dollars in venture capital are at a decade high, slowly rising to its historical high during the dot-com bubble. However, while invested dollars are rising, deal count is decreasing. The availability has allowed startups to stay private longer than ever before and made the path to IPO a much longer time horizon.

The nomenclature around investment categories is constantly shifting; currently, there are 3 commonly referenced stages within venture capital:

• Pre-seed/seed

• Early stage (typically Series A-C)

• Growth (typically Series D+)

Venture capital firms lie anywhere on or between these stages and fill voids in the market for financing.

The earliest stage of venture funding, the pre-seed/seed stage, is typically occupied by friends, family, and angel investors, with increasing competition from institutional funds. Seed stage companies are newly formed companies with little to no operating history. Investments at this stage are extremely network-driven and rest entirely on concept viability and the confidence in the founding team as determined by an investor.

Early stage capital is primarily allocated toward market research, product development, and business enhancements. Investors in the early stage seek companies that have a completed business plan and demonstrate some level of concept validation through key customers but are usually not cash flow positive. Businesses in this stage need cash to fuel staffing requirements, capacity/inventory, and other strategic capital expenditures.

Growth stage investors focus on companies with proven business models with a clear path to profitability. Firms investing in this space seek companies with existing sales and a strong pipeline. Companies seeking funding in this round use the raise to aggressively penetrate the market. Subsequent rounds of growth stage capital, sometimes referred to as late stage capital, are reserved for relatively mature companies seeking to raise large rounds for specific strategic initiatives (like geographic expansion, acquisitions, investment in PP&E, etc.) that will further clear the path to market dominance and a subsequent exit.

While these three categories all typically encompass primary capital used to fund company operations and initiatives, growth and late stage capital rounds often include secondary shares where founders, employees and early investors also sell their holdings to later investors. Secondary shares can also be available through broker-dealers or exchanges like SharesPost and EquityZen.

As part of any healthy portfolio, diversification is key. Based on your existing portfolio and exposure, you may benefit from investing on either end of the venture capital cycle. If you are interested in learning more about how you can tap into the rapidly growing venture capital market, get in touch with us at lvam@laconiacapitalgroup.com.

Originally published in the October 2018 LVAM Newsletter.

Generally speaking, a fund-of-funds is any group that invests in other funds. In venture capital specifically, funds-of-funds function as limited partners (with very few exceptions). Those limited partners receive reports and due diligence documentation whenever the fund is making a new investment as well as periodic reports on the performance of the portfolio as a whole.

Investing in venture capital funds either directly as a limited partner or through a single fund-of-funds can be a great way to diversify your overall portfolio. The high level of risk associated with direct startup investments can make it difficult to start a venture capital arm of your own. Investing in or as a fund-of-funds mitigates that risk tremendously as you are investing in the venture capital fund’s entire portfolio, which could represent dozens of startups. You still have the ability to capitalize on the oversized returns that come from successful venture investing without having to take on the same degree of risk.

The most straightforward funds-of-funds only invest in venture capital funds, but many groups are using a hybrid strategy where part of their portfolio is made up of venture capital funds and part of it is direct investments in startups.

If directly investing in startups is something that interests you, but you don’t have the team in place or knowledge base to properly source and analyze that type of investment, co-investing can be a great option. Essentially, a fund you are involved with may find an interesting company and decide to make an investment. However, it is extremely uncommon for one venture fund to be the only investor in a round of startup funding.

That’s where a hybrid fund-of-funds can come in and make an additional direct contribution to the round. It is a simple way to invest in a startup that has already been vetted and fully analyzed by a trusted venture group.

When you become a limited partner in a venture capital fund, it opens you up to a whole new world of tech startup knowledge. Doing so can be the ideal first step on the path in getting venture capital exposure.

If you are interested in learning more about how to invest in or set up a fund-of-funds, feel free to contact us at lvam@laconiacapitalgroup.com.

Originally published in the September 2018 LVAM Newsletter.

Venture capital can be a daunting asset class to analyze. If you are familiar with private equity, you are probably used to judging a company based on detailed financial modeling. With venture capital deals, the numbers and parameters you have for mature companies just don’t exist yet. That doesn’t mean that you can’t conduct a thorough analysis of a company before investing. What it does mean is that you need to have a formal and disciplined process for due diligence that is tailored specifically to early stage companies and startups.

At Laconia, we like to break our diligence into three stages. During the first stage, we focus on the business’s operations, and perhaps more importantly, the management team’s understanding and thought process around their product and strategy. While we do look at financial models at this point, we are looking at them with a grain of salt. We want to make sure there is a solid sales process in place and a good understanding of how the company is going to prioritize customers and increase their market share. In this stage, we also do our own research into the market size and competitive landscape, and take a detailed look at the company’s capital strategy.

During the second stage, we shift our focus to customers and product development. At this point, besides looking into the product development roadmap, we like to introduce the company we are working with to potential customers from our network. Not only does this allow us to add value to the relationship throughout the due diligence process, but it also allows us to get real time market insight and understanding of the sales process. Product market fit is one of the most important things to consider when evaluating a venture deal.

The final stage of our due diligence process mostly consists of tying up any loose ends. If we get to this point, we already have a good understanding of the product, and we have a technical expert take a look at the details of the tech stack and software architecture to make sure everything is sound. We also conduct reference calls for the main team members and take a look at the company’s legal documents. We try to keep the process as efficient as possible to respect everyone’s time while still being thorough. We strive to keep the due diligence process productive and painless for both ourselves and the entrepreneurs we work with.

If you are looking to make venture capital investments, a thorough due diligence process is essential. Don’t assume that just because a company is nascent in its development that you can’t do the research and ask the questions to make a smart investment decision. We have found that as long as you stay disciplined with a proven process, even this seemingly enigmatic asset class can be analyzed.

If you would like to learn more about our process, or are interested in collaborating with us on due diligence for your own venture investments, feel free to reach out to us at lvam@laconiacapitalgroup.com.

Originally published in the July 2018 LVAM Newsletter.

If you are looking into venture capital as an investment opportunity, you are likely aware of other options like private equity and real estate. While these alternative asset classes share some similarities (illiquidity, long investment holding periods), there are distinct differences in structure and investment strategy that are important to consider as you dive into venture capital investing.

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal takes a critical look at the differences in venture capital and private equity, specifically when it comes to returns. The biggest takeaway from their research is that venture capital investing vastly outperforms private equity when it is successful. However, the returns are more volatile, with longer holding periods. This time horizon stems from the fact that venture capital firms invest in early stage companies that may be pre-revenue, and venture investors only make money when those companies are acquired or go public. Thus, venture capital gets in early on high-growth opportunities, in contrast to private equity, which makes shorter term investments in mature, private companies.

Real estate investing presents its own set of variables. Real estate investors make money from regular payments and a long term increase in property values (although increases in property values rarely result in capital gains). This means that you can have steady cash flow with less market volatility. However, you don’t have the opportunity to see the tremendous returns that venture capital is known for.

As you take steps to diversity your portfolio, it’s worth taking the time to evaluate the different asset classes available to you. A side-by-side comparison of alternative assets, like the chart below, is a good starting point to figure out what type of investing is right for you.

If you are interested in learning more about the role of venture capital within family offices, feel free to contact us at lvam@laconiacapitalgroup.com.

Originally published in the June 2018 LVAM Newsletter.

One major challenge when investing in venture capital is to remember to stay patient when facing a timeline that could take years to see positive cash flows. This illiquidity is mainly due to the amount of time it takes a startup to go public or even get acquired.

As of 2017, the median time for a startup to exit via an IPO was 8.2 years. As more late stage startups are choosing to raise more capital and lengthen their runway rather than exit, liquidity has become the single biggest challenge for venture capital firms. Even success stories like Buzzfeed, Qualtrics and AirBnB have chosen to raise more money late in the game instead of going public, despite consistent revenue and high valuations. The reasoning is simple: they want more time. By staying private longer, these startups hope to establish profitability and avoid the pitfalls they’ve watched other tech startups like Snap run into.

While the long road to an IPO can seem daunting, it actually doesn’t spell trouble for venture capital investing. In the beginning of a VC portfolio’s lifetime, it will see little to no net cash flow as investments are being made, resulting in greater cash outflow than inflow. As portfolio companies start to exit, the portfolio moves into a harvest period in which earlier unrealized gains are realized. At this point, a venture capital portfolio can be self-funding where the realized gains now fund the newer venture investments. By the way, this is the exact same j curve investment horizon that private equity and real estate experience. In this regard, venture capital investing is exactly the same as investing in private equity or real estate. More importantly, investment returns generally increase with the degree of illiquidity for which venture capital historically has had the best performance.

If the long-term outsized returns associated with venture capital investing don’t provide enough incentive to take on the risk associated with venture’s illiquidity and timeframe, there are other options to help reduce the investment frame and risk. However, it is usually done with a concomitant reduction of risk. As highlighted last month with the Spotify IPO, secondary markets for late-stage venture investments have matured and proliferated. These markets can allow you to either invest at a later-company-stage or achieve partial or even full liquidity on an early investment without an actual exit event like an IPO or acquisition. In addition, funds that focus on late-stage secondary transactions have also begun to emerge, offering smaller investors the chance to participate in later-stage venture opportunities with shorter investment windows.

If you are interested in learning more about the role of venture capital within family offices, feel free to contact us at lvam@laconiacapitalgroup.com.

Originally published in the May 2018 LVAM Newsletter.

In venture capital, returns follow the Pareto principle - 80% of the returns come from 20% of the investments. Early-stage venture capital firms have often been attractive to investors, providing lower valuations with the opportunity to obtain significant equity ownership in portfolio companies.

In today's Topic of the Month, we take a deeper dive into the numbers posted for a couple investments prior to their IPOs and acquisitions.

Facebook’s $22B acquisition of WhatsApp in 2014 is the largest private acquisition of a VC-backed startup. It was a huge win for Sequoia Capital, the company’s only venture investor, which turned its $60M investment into $3B. At the time of acquisition, Sequoia owned 18% of the company and its shares were valued at $3bn, representing a 50x return overall.

Zynga

Zynga’s $7B IPO in 2011 made social gaming history — and was an important moment for Union Square Ventures, which owned a 5.1% stake worth $285.1M when the company went public. USV lead the company's $10mm Series A round when the company was less than a year old and made a 75-80x return on the original investment.

After taking a closer look at some of the largest VC exits, it is evident that VC investments provide an opportunity for outsized returns and are a result of detailed research/due diligence, strong convictions, and committed follow-through. If you are interested in learning more about the role of venture capital within family offices, feel free to contact us at lvam@laconiacapitalgroup.com.

Originally published in the April 2018 LVAM Newsletter.

A term sheet is often exactly that: a sheet full of terms. As an investor, these terms go beyond simply outlining the percentage of equity received. Investor rights establish the non-equity provisions that investors have to protect against downside risks, manage strategic decision-making, and mitigate future dilution. It is also imperative to understand the meaning of these terms to understand how your investment fares against other investors from preceding or succeeding rounds.

Valuation

An important aspect of any term sheet is the valuation. A pre-money valuation is the value of the company before cash is invested. Post-money valuation is typically the pre-money valuation + the newly invested capital. An investor needs to know how much their capital is impacting the post-money valuation to understand how much of the company’s overall valuation is composed of their investment.

Preferred versus Common

The type of equity investors usually purchase is “preferred” stock. The difference between common stock and preferred stock is pay-out priority. Preferred stockholders receive proceeds before common stockholders, thereby ensuring that investors are compensated before common stockholders during an exit scenario. This effect is typically compounded by liquidation preferences and participation rights.

Liquidation Preference

Liquidation preferences are seen as a provision for minimizing downside risk during an unfavorable exit. In the event that the company is under distressed sale/merger or bankruptcy, a liquidation preference stipulates that an investor’s original capital investment must be returned before any other equity holders participate in the exit. Some investments may include multiples on the original investment value, which mean 2x, 3x, or more of the initial investment must be paid back to the investor before other shareholders can participate. An investor who holds both preferred equity and a liquidation preference will receive the negotiated multiple value of their investment in addition to any equity ownership they hold in the company.

Voting, Co-Sale, Drag Along, and Pro-Rata Provisions

Voting rights give investors the ability to influence decision-making within a company. Typically, investors will negotiate for voting rights irrespective of what type of equity holder they are (common vs. preferred). However, beyond just having voting rights, term sheets outline provisions that dictate how and when votes will be counted. These situations can include: changes to corporate bylaws, issuing stock, transaction approvals, and changes to the board composition. On that note, early stage investors also usually require board seats; the number depends on the existing board size and the investment amount.

Co-sale provisions (also known as “tag-along rights”) allow investors to sell their shares on a pro-rata basis alongside founders in the event that the founders seek to sell their shares to external investors. This provision gives investors a partial exit opportunity alongside the founders if there is a compelling opportunity present. If the sale is greater than 50%, it may trigger a liquidation event clause in the term sheet, forcing the proceeds of the sale to be distributed to the shareholders. These provisions help ensure that investors are protected from the unfavorable outcome where the founders decide to walk away from the company. Drag-along provisions operate in the other way, wherein a majority shareholder can force the minority shareholder into a sale.

Finally, as an investor it is important to consider how an investment will fare after future financing rounds. Pro-rata rights give investors the opportunity to invest in future rounds of financing in order to ensure that equity held today will not be diluted severely by subsequent rounds.

If you are interested in learning more about the intricacies of a term sheet, feel free to contact us at lvam@laconiacapitalgroup.com.

Originally published in the November 2018 LVAM Newsletter.